[ad_1]

Mike Groh sat in the front row of the upper deck that Sunday, wind whipping on a 26-degree December afternoon at Giants Stadium. And Groh, five days shy of his 15th birthday, couldn’t have been happier. With his dad next to him, he admired the football royalty performing on the field — Phil Simms, Harry Carson, Lawrence Taylor, and the rest of the 1986 Giants.

It was the perfect birthday present — a flight from North Carolina to watch his Giants pound the Cardinals, launching them toward their first Super Bowl title; a pregame diner meal near the stadium; and even a game-worn L.T. jersey, courtesy of his dad’s buddy, Bill Parcells.

Thirty-six years later, that jersey hangs in Groh’s office at the Giants’ training facility, across a parking lot from where the old upper deck once stood. As new head coach Brian Daboll’s first wide receivers coach — tasked with molding Kenny Golladay and Kadarius Toney, who both underachieved last season — Groh is reestablishing his family’s connection with the Giants, a franchise that helped him fall in love with football.

Recently, Groh told his dad something he had never shared.

“He said it was the one team he always hoped he could coach for,” said Al Groh, who coached for the Giants from 1989-91 and with the Jets from 1997-2000.

BUY GIANTS TICKETS: STUBHUB, VIVID SEATS, TICKETSMARTER, TICKETMASTER

For Mike Groh, at age 50, this is also the next step in his latest career rebuilding mission, two years after the Eagles awkwardly fired him as offensive coordinator — a moment that resembled Al being forced to fire him at the University of Virginia in 2008. With a Super Bowl ring, three college national titles, and far too many moves around the country, Groh’s coaching life has brought him “the highest of highs and the lowest of lows,” he said.

But now, Groh is starting fresh in a place that feels comfortable, back in New Jersey, where he made high school football history with Randolph in 1990, the same season Al won a Super Bowl as the Giants’ linebackers coach.

Groh taking this job under Daboll “was him coming home” to “where his memories are,” said Kevin Bray, one of Groh’s best friends from Randolph — a group Groh has leaned on through his coaching ups and downs. And if Groh and Daboll win big — with a team that has failed miserably over the past decade — New Jersey will be home again for a while.

Groh has witnessed Giants glory. He was a ball boy in 1990 training camp, back when Bill Belichick talked football with his dad at the kitchen table. A few months later, Groh stood in the Giants’ locker room in Tampa, Fla., after they won the Super Bowl, watching his idols celebrate. That L.T. jersey in his office is more than just a memento. It’s a motivator.

“Those guys were giants — no pun intended — in your mind,” Groh said. “We’re here to get it going in the right direction. I’m excited to be a part of getting back to, really, Giants football. For all the good memories, it feels good to be back [in New Jersey], but hopefully to make some new ones.”

***

A voice piped up from the back seat.

“I forgot my birdhouse!”

“All right, well, go get it,” Groh told his 8-year-old son, Cort, short for Albert Michael Groh IV.

It was the last day of camp earlier this month in Indianapolis, and Groh was picking up his two kids, Cort and 5-year-old daughter Quinn. The next day, they’d all pile in — Groh; his wife, Elena; the kids; and two dogs — and drive 12 hours to their new home in Summit. Another move for Groh, who coached the Colts’ receivers the past two seasons.

But first, Groh turned around to check out his son’s birdhouse.

“Hey, Cort, that’s awesome, bro!” he said.

Groh loathes the headaches of moving, but he’s gotten used to them, even as all the boxing and unboxing adds more grays to his salt-and-pepper beard. Still, he tries to never look back, even when change stings.

It seemed he had found solid footing in Philadelphia. He joined the Eagles as receivers coach in 2017 and immediately won a ring. When Frank Reich became the Colts’ head coach, Groh took over as coordinator. Though Doug Pederson continued to call plays, the Eagles finished 10th and seventh in Pro Football Focus’ offensive ratings from 2018-19.

Pederson even publicly said Groh would return in 2020. Owner Jeffrey Lurie disagreed — and Groh was gone. If Groh harbors emotions about the firing, he declined to reveal them.

“I think it’s probably best that I just … ” Groh said, pausing for a moment, “keep those feelings to myself at this point.”

Groh’s reunion with Reich in Indianapolis wasn’t as jarring as his firing from Virginia in 2008 — the first time he had to relaunch his career and reprove himself.

After playing quarterback at Virginia and working 2½ years as a stockbroker in Richmond, Va., Groh started coaching in 2000, as a low-level assistant for his dad, then in his lone season as Jets head coach. Groh followed Al to Virginia in 2001 and became offensive coordinator in 2006. But because of state nepotism laws, he reported to athletic director Craig Littlepage, a former Rutgers basketball coach, who forced Al to fire Mike after three uneven seasons.

That father-son conversation still upsets Al, who called it “the worst.”

“It was very hurtful, and that’s because it wasn’t my idea,” he said of the firing. “I think Michael’s career accomplishments from that point have shown the folly of the athletic director’s knowledge of football.”

Groh felt adrift — 37 years old, just married, and wondering what was next.

“I think that was probably the hardest moment from a career standpoint,” he said. “Because I really had only ever worked for my dad in the profession. I didn’t have a lot of contacts. Obviously, it didn’t end well [at Virginia]. Trying to figure out what the next step was from there was certainly a challenge.”

In 2009, he landed at Alabama as a graduate assistant under Nick Saban, who, like Al, comes from the Parcells and Bill Belichick coaching tree — along with Daboll. (Al and Saban spent one season together, 1992, on Belichick’s Browns staff.) As he restarted his career, Groh opened his mind to Saban’s ideas. He still has notebooks full of information he collected that season.

And he still lives by advice Saban gave him about not looking back at mistakes or ahead to aspirations: “Just do a really good job with the job you’ve got — and things usually work out for the best.”

That season in Tuscaloosa also began Groh’s vagabond coaching life. From 2010-16, he worked at Louisville, back at Alabama, and in the NFL with the Bears and Rams, before the Eagles hired him. Since leaving Virginia, he’s made eight stops at seven different places in 14 years.

And Groh started the trend at Alabama — and eventually elsewhere — of an established coach taking a low-level job at a big-time program to rehabilitate his career.

“I really was a trailblazer in the way that coaching staffs are put together in college football,” he said.

He won three national titles in three seasons at Alabama. (He was receivers coach/recruiting coordinator from 2011-12.) After the first championship, in that rehab year, he flashed back to his dad bringing him onto the field when the 1990 Giants won the Super Bowl.

As Groh soaked in Alabama’s celebration at the Rose Bowl, he stood with his dad, wife, and mom, Anne. Then he turned to Al.

“Dad, remember the Super Bowl?” Groh said. “Well, now I paid you back.”

***

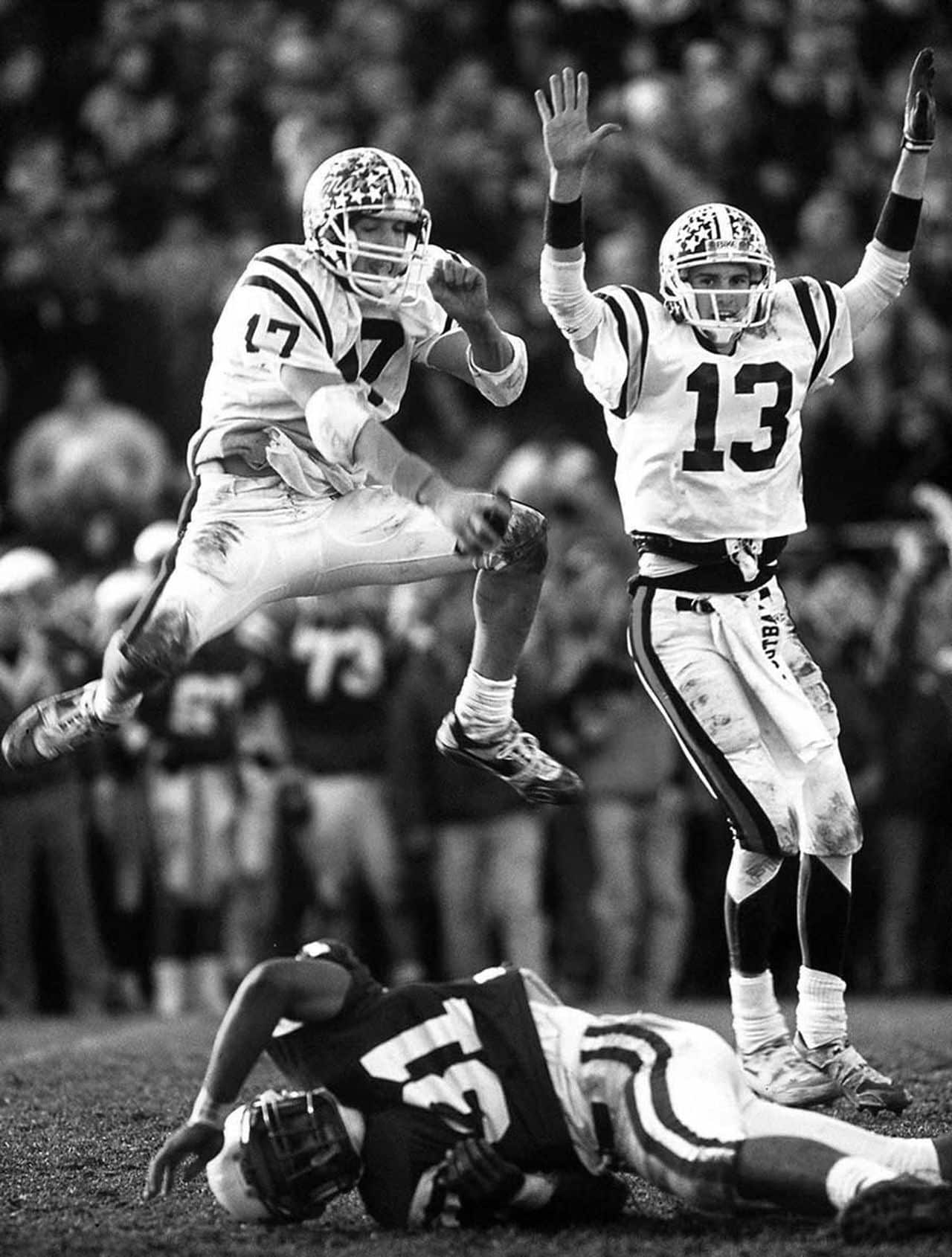

Mike Groh (13), who starred at Randolph, became a New Jersey high school football legend with his game-winning field goal against Montclair in the 1990 state championship game.

The night before the biggest game of Groh’s life, he sat in the den at home with his dad.

“Before you go to sleep, think about how you’re going to be prepared if you have to throw one or kick one to win it at the end,” Al told him.

“Dad, I’d rather be throwing it than kicking it,” Mike replied.

“I’m sure you would,” Al said. “But it might go either way. Just be ready for whatever comes up.”

The next day — Dec. 1, 1990 — Groh and Randolph would face Montclair in the state championship, while trying to set a state record with a 49th straight win and playing for the memory of head coach John Bauer Sr., who died two weeks earlier.

Groh, a senior quarterback and kicker, rarely had to attempt field goals because Randolph’s offense was so prolific. But before boarding the bus to Montclair that Saturday morning, Groh sneaked in a few extra practice field goals.

“Weird,” thought Bray, a right tackle and linebacker.

Meanwhile, Al was at Giants headquarters, prepared to miss the game. The Giants were playing in San Francisco that Monday night and had a Saturday flight to catch. But Belichick surprised Groh by arranging for a police car to bring him from Giants Stadium to Montclair, so he could catch some of the game. He watched from one end zone, under the goal posts.

When Al had to leave for Newark Airport, Montclair was leading and driving. He got on the plane feeling anxious. Somewhere over Utah, he picked up the seat-back phone and used his credit card to call home. Anne answered.

“You just need to talk to Michael,” she said, declining to reveal more.

He was at a teammate’s house, she said. Al tried him there. The phone rang. Al’s mind raced.

“Dad, remember what you told me last night?” Mike said when Al finally reached him.

“Yeah, Mike, what happened?” Al said.

“I kicked one on the last play of the game to win it,” Mike replied.

Al — who still gets goosebumps every time he tells this story — shouted with joy on the plane. Giants players who overheard the call erupted in cheers for one of their favorite ball boys. Mike’s 37-yard field goal as time expired gave Randolph a 22-21 win — and made him a New Jersey high school football legend.

That iconic game and the Giants’ Super Bowl victory also forever made North Jersey a joyous place for Groh — finally, somewhere he could call home.

He never truly had that before 1989, when he arrived in Randolph. Growing up, he moved around the country as his dad changed jobs — Virginia, North Carolina, Air Force (under Parcells), Texas Tech, Wake Forest, the Falcons, and South Carolina. Randolph was Groh’s third high school. He arrived as a junior, fresh off a South Carolina state championship.

He told Bray, one of his new neighbors in Randolph, how hard all the moving was. But as it turned out, Randolph gave him just what he needed.

“In Randolph, football was a big deal,” Bray said. “That’s kind of the language that we all spoke.”

Groh dove into Randolph’s grueling summer workouts, even exposing teammates to country music on the locker room stereo — a holdover from his time in the South. Groh gained teammates’ respect by showing up every day in the summer for 6½ hours of lifting weights and learning plays in Randolph’s complex, passing-focused offense. At night, he and his new friends hit the Pizza Palace on Sussex Turnpike to make that evening’s plans over slices.

“He fit in on Day 1,” said Mike Lyons, a Randolph assistant coach since 1987. “Just what we were looking for.”

So even as Groh’s coaching career dragged him around America, he carried Randolph with him, along with that game-worn L.T. jersey. He stayed in touch with friends like Bray and Darren Tappen, a basketball teammate, inviting them to Alabama’s national title games and the Eagles’ Super Bowl. He never got rid of his Randolph helmet or jersey. He kept a tape of the “Miracle at Montclair” game and a framed photo of him leaping to celebrate the winning field goal.

“It’s kind of a grounding thing,” Tappen said of Groh’s continued connections to Randolph. “I think it’s very important. It’s the one thing he knows that he can get.”

***

Groh was a clean-shaven high school kid in the summer of 1990, when he worked Giants training camp as Belichick’s ball boy.

He threw passes to defensive backs during drills. He got players’ cars washed, cleaned their lockers, and carried their pads off the field. From across practice, Al admired how easily his son — growing into his own man — interacted with the players.

And while Groh said coaching Giants practices now doesn’t feel like “a déjà vu moment for me,” he still retains all those memories and indelible images from 1990.

Now, at age 50 — though he doesn’t feel it — he is secure in his accomplishments, despite the bumps. His three Alabama rings alone are “more than most coaches can say they ever got to be a part of,” he said.

But he’s not done, as he prepares to mold one of the 2022 Giants’ most intriguing position groups, in a critical bounce-back season for Golladay and Toney. Groh hopes to mimic the transformational results he got last season from Colts receiver Michael Pittman Jr., who had 1,082 yards and six touchdowns — more than double his production as the 34th overall draft pick in 2020.

“I feel like I’ve got a lot of good years left — hopefully the best years professionally and personally,” Groh said.

But first, Camp Daddy — which is what Groh calls this stretch before Giants camp begins in late July. Elena got a job working on the business side of the fashion industry in Manhattan, so Groh is watching his two kids.

They’ll explore Summit and visit his parents — Poppy and Gigi, as they’re now called — at their retirement home in Hingham, Mass., not far from where Mike’s younger brother, Matt, is chasing his third Super Bowl ring in his debut season as Belichick’s director of player personnel.

They’ll also make the 30-minute drive out to Randolph — where Groh plans to catch a football game this season — and stop by the Pizza Palace. It’s a regular trip when Groh is in town, to visit with Vito Donato, whose family has owned the restaurant for 51 years.

“You see him come through the door, and you want to give him a big hug and say, ‘Welcome home,’” said Donato, who was a year behind Groh at Randolph High.

Some of Groh’s Randolph buddies have moved away — Tappen lives in Arizona, Bray in Connecticut — but in the summer, they always reunite at a beach house in tiny Gearhart, Ore., for golfing, sturgeon fishing, and bonfires. Blissfully, cell phone service is spotty.

“It’s refreshing to get out there, kind of off the grid,” Groh said.

Then it’s back to New Jersey, to his family, to a dream job that he hopes can keep them all here longer than two years this time. When he landed this job, he pulled up a group text thread of his Randolph friends. He wanted to let them know he was coming home.

And he knew just how to do it, with another indelible image. Instead of writing anything in his message, Groh just texted a photo — of a Giants helmet.

Thank you for relying on us to provide the journalism you can trust. Please consider supporting us with a subscription.

Darryl Slater may be reached at dslater@njadvancemedia.com.

[ad_2]

Source link